FANTASIA OBSCURA: The Almost, Sorta-Kinda, Not-Quite ‘Star Wars’ Knockoff

There are some fantasy, science fiction, and horror films that not every fan has caught. Not every film ever made has been seen by the audience that lives for such fare. Some of these deserve another look, because sometimes not every film should remain obscure.

Sometimes, you place your monies, you takes your chances, and you have to suck it up when you roll snake-eyes…

Damnation Alley (1977)

Distributed by: Twentieth Century Fox

Directed by: Jack Smight

Forty years ago, a seminal work of genre film was released to an unsuspecting world:

Star Wars became a sensation on its release and enticed millions who have watched the film — some of them hundreds of times. The wonder and enchantment the film inspired drew legions of fans who have embraced the film, enough so that a recent sequel to the movie became one of the highest grossing films of 2017, if not the highest grossing.

To its fans and devotees, it seems alien that anyone could ever watch their favorite film and not fall in love with it. The idea that anyone would not have become obsessed with it is just inconceivable.

They probably never met the management of Twentieth Century Fox circa 1977, apparently, who thought this film would be their genre break-out that year:

We open here on Earth in the present at what the onscreen chyron helpful tells us is, “123rd Strategic Missile Wing, Tipton AFB, California.” We watch what looks to be a maybe-too-casual work environment for an ICBM base under the credits, before we see Major Eugene Denton (George Peppard) and 1st Lieutenant Jake Tanner (Jan-Michael Vincent) assume their posts at their launch station.

After a quick interaction with Airman Tom Keegan (Paul Winfield), Denton lets Tanner know that he’s put in to be paired up with a different missile man on duty, showing us that these two aren’t supposed to be together were it not for circumstances beyond their control.

And when we talk “circumstances,” we mean it, as in a first strike by the USSR’s incoming ICBMs. Coldly and professionally, Denton and Tanner launch their 10 birds (which we see through lots of DoD stock footage of Atlas and Titan II launches) while the United States gets bombed back beyond the Stone Age, via lots of DoD footage of nuclear tests. (Interestingly, there are anti-missile defenses deployed, and yet 40% of the Soviet warheads hit their targets; make your own “star wars” joke here, folks.)

So, having seen close to 85 million die before the end of the first reel, we get told through onscreen text that radioactive dust enshrouds a world knocked off its axis. At which point, we revisit Tipton, where Tanner and Keegan are mustered out of the USAF but still hanging around because, no, there really is nowhere else to go, while Denton and Lt. Perry (Kip Niven) tool around in the workshop on a project.

A project that becomes essential to their survival, and the plot of the film, when another airman accidentally blows up the silo complex with a cigarette and a copy of Playboy (no, don’t ask, really). Having nothing to keep them there, the four survivors head for the one place that still sends out an active radio signal regularly, the last bastion of civilization: Albany, NY.

Now, no disrespect to the fine folks of the Capital Region, but, well… to be honest, if Albany is the last bastion of civilization, the Russians must have used a LOT of bombs on the rest of the country.

It’s at this point the real star of the film comes on screen: the Landmaster, designed for the film by Dean Jeffries, the father of the Monkeemobile. There’s actually two that roll out of Tipton, but one is claimed by a tornado (along with Perry), leaving only one machine to make its way east.

There’s a brief stop in what’s left of Las Vegas, where they pick up survivor Janice (Dominique Sanda) before heading to Salt Lake City, where Keegan meets a horrific end at the mandibles of some horrifically rendered roaches (and starts a long streak of Paul Winfield roles where he never sees the end credits):

We end up with a quick stop to pick up young survivor Billy (Jackie Earle Haley) and a sequence of shots that encourage the audience to whine, “Are we there yet?” successively before the film pulls out a Deus ex Nihil ending that leaves a few questions, like, how could the good money at Fox gone to this film?

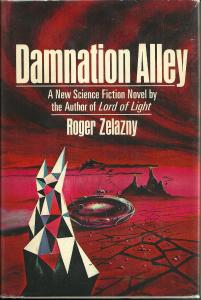

One possible theory is that the original source novel by Roger Zelazny, which had as its original story a more of an Escape from New York-meets-Mad Max kind of plot, may have been more relatable to Fox’s executives than the story about robots finding a mystic knight on a desert planet that George Lucas presented. And perhaps if the more faithful screenplay that Lukas Heller started with had not gotten a re-write by Alan Sharp, there might have been a better film at the end of the process.

Unfortunately, the “brain trust” couldn’t stop meddling there. Convinced that there needed to be more glowing effect-sparkling skies in every shot, and just blown away by the Landmaster, notes from the studio forced the film to add shots of the vehicle and re-master scenes so that glowing skies would be more prominent. This added almost a year to post-production, and in addition to costing the film time (forcing it to premiere in October of 1977), it also meant many scenes that would have made the characters more than just empty tics and talking points never left the edit bay.

Considering these were the same execs who allowed Lucas to keep most of the marketing revenue for Star Wars, one has to really wonder about leadership at the studio at the time.

The end result was a film that was not only disjointed and half-baked but had its popped seams easily seen by the audience. It was filmmaking by corporate committee; whatever good anyone involved could have brought to the table was lost in studio notes sent by folks who tried to second guess the audience, and did badly doing so. About the only contributor whose work was allowed to flourish was Jerry Goldsmith, who managed to give the film a better score than it deserved.

If only the folks at Fox could have been more hands-off; one could only imagine what might have happened had someone been allowed to do a genre film there with minimal interference…

…ohwaitaminutehere!

NEXT TIME: Why some people blame Jodie Foster for what Bill Shatner did to Elton John.