FANTASIA OBSCURA: Adam West’s Pre-‘Batman’ Launch Into Space

There are some fantasy, science fiction, and horror films that not every fan has caught. Not every film ever made has been seen by the audience that lives for such fare. Some of these deserve another look, because sometimes not every film should remain obscure.

Sometimes, the greatest adventure comes about from asking, “What if it had ended up differently?”

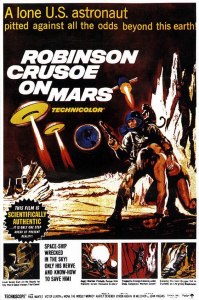

Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964)

Distributed by: Paramount Pictures

Directed by: Byron Haskin

Please note that this is not the film we teased last week; we’re delaying that to look at this movie, prompted by the sudden news of Adam West’s passing.

“What if?” It’s a question that can lead to tremendous scientific advancements, or it can push the boundaries of our culture by producing exciting art.

It can also be useful to ask this question as we look back on the earlier answers to it, to imagine how things could have turned out differently. This is exactly what Philip K. Dick and Uatu the Watcher aim to do, and it’s worth considering this week in light of recent events.

Here’s a little context:

Our film opens a few years from the present in an unidentified period when Mars Gravity Probe 1 is surveying the planet nearest us. It’s a joint missions project from the US, commanded by USAF Colonel Dan McReady (Adam West), with USN Commander “Kit” Draper (Paul Mantee) as the only other crew. Also aboard the craft is a wooly monkey, Mona, whom McReady decides en route not to eject to the surface of Mars, believing that they have enough animal data. This will allow him to take her home as a pet instead.

It’s a nice thought, but it doesn’t happen. A large planetoid bears down on the Mars Gravity Probe 1, and in the process of collision avoidance, the craft gets dragged into Mars’ gravity well. McReady gives the order for both self-contained astronaut pods to eject to the surface, hoping to save the main ship from crashing and expecting both men to use their survival skills to stay alive until a rescue can come for them.

From there, we follow Draper, whose craft crashes on the lunar surface. This puts him at a disadvantage in removing much of the gear and protection his lander could have given him. But his training kicks in, and with some good luck, he manages to go from being totally hosed to doing okay.

Finding rocks that release oxygen when heated, he supplements his air tanks. The pools of standing water he encounters contain a plant useful as both food and cloth, enabling Draper to weave things like a hat.

What he doesn’t have, however, is company. Sadly, McReady’s lander crashed on impact, killing him, although Mona survived. This gives Draper someone to talk to between essential life-sustaining duties and making log entries. But not having anyone respond to him starts to eat away at the lone human survivor.

This changes when an alien from one of the stars in Orion’s belt (Victor Lundin) escapes from the slavers who brought him to Mars to mine for minerals the other aliens wanted. Named “Friday” by Draper, the two go from uneasily eyeing each other to fostering a decent friendship as they try and stay hidden from the slavers and make an effort to survive a hostile planet.

And such a hostile world it is. Haskin’s decision to film a large percentage of the picture in Death Valley National Park helps give the film a feel that would not have been possible shooting only at the Paramount sound stages. Aided immensely by a fantastic score from Van Cleave, the movie has a serious tone that demands you pay attention to what’s going on. And, for the most part, it deserves your attention.

Where it fails — in the script and story — both are and are not the film’s fault.

The source material, The Life and Adventure of Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe, is a classic that could be better related to in an earlier time. While tales of survival and making order out in the wilderness have a strong universal appeal (think Lost in Space and Gilligan’s Island), the whole concept of Friday and Crusoe’s relationship can be difficult to look at in a post-imperial setting.

Even if you try to change the dynamic to give the two characters more equal footing, there’s still the undercurrent therein that we’re looking at “the white man’s burden” in most versions of the story. This can be distracting, and the script from Ib Melchior and John Higgins fails to avoid it here. (Even the more robust efforts to address this issue, such as 1975’s Man Friday, don’t always get this right.)

There’s also the claim the film makes of being “scientifically accurate,” which may be hard for modern audiences to accept. Keep in mind that, up to 1964, most of what we knew about Mars came from Earth-based observations. What data we had was limited to what could be gathered from close to 100 prior years of observing the planet through telescopes from millions of miles away.

The great irony is, come 1965, Mariner 4 would g o into orbit around the Red Planet and chuck away years of assumptions based on faulty observations. (Which means, for all we know, later data from Mars may make Ridley Scott’s The Martian face the same fate this film did.)

o into orbit around the Red Planet and chuck away years of assumptions based on faulty observations. (Which means, for all we know, later data from Mars may make Ridley Scott’s The Martian face the same fate this film did.)

Which prompts an interesting “What if?” question: What if the film came out after we got better information about Mars from Mariner 4? Would the movie be as well remembered by its diehard fans as a contemplative piece of science fiction that eschewed most of the tropes of the time and tried to give us a serious story of survival on an alien world?

As of this moment, though, a different “What if?” comes to mind: What if Adam West had more to do in the film?

Because West is essentially in just the setup for the film (and in one fever dream further in), his time onscreen hardly measures to that of Mantee, but his presence is certainly felt. Given a choice between who you’d want to watch survive Mars, most people might want to follow him versus Mantee. Whether we end up with Draper by design, in an attempt to give the film some sense of shock and realism by taking out the more compelling actor too early on, can be debated.

In a complete consideration of the scenario, the film got notices but not a lot of revenue. Mantee and Lundin went back to doing mostly TV work after the film’s release, as did West, with Lundin playing a “native” in a number of episodes of Batman a few years later.

But what if West had been cast as Draper, or if the script had made McReady the sole survivor? Could West have gotten more film work as the charismatic lone astronaut the film follows? Would Batman have been the same phenomenon had the other actor up for the role of Bruce Wayne, Lyle Waggoner, gotten the role of Bruce Wayne instead? And what would West’s career have been as robust as it was had he not become the face of Bat-mania?

These are questions to keep your mind busy as you stare into the night sky looking for a bright red dot, trying to deal with loss…

NEXT TIME: Barring further bad news, we work with that real head case that maybe could have used a few more laughs.