Songwriting, Spirituality, and Satisfaction: An Intimate Conversation With Bobby Hart

Bobby Hart is the cowriter (along with longtime musical collaborator, the late Tommy Boyce) of some of the Monkees’ most famous songs, including “(Theme from) The Monkees,” “Last Train to Clarksville,” “(I’m Not Your) Steppin’ Stone,” and “Valleri.” In his new book, Psychedelic Bubblegum: Boyce & Hart, the Monkees, and Turning Mayhem Into Miracles, Hart shares behind-the-scenes tales from his lifetime in the music business, reveals the story of his own spiritual journey, and offers guidance to readers hoping to find fulfillment in their personal and professional lives.

Bobby Hart is the cowriter (along with longtime musical collaborator, the late Tommy Boyce) of some of the Monkees’ most famous songs, including “(Theme from) The Monkees,” “Last Train to Clarksville,” “(I’m Not Your) Steppin’ Stone,” and “Valleri.” In his new book, Psychedelic Bubblegum: Boyce & Hart, the Monkees, and Turning Mayhem Into Miracles, Hart shares behind-the-scenes tales from his lifetime in the music business, reveals the story of his own spiritual journey, and offers guidance to readers hoping to find fulfillment in their personal and professional lives.

REBEAT: Congratulations on your book! What led you to write it, and what was the writing process like?

BOBBY HART: It’s something I’ve been thinking about doing, and doing little bits and pieces of, for many years, actually. I got serious about it maybe 10 years ago and did a version that I wasn’t happy with when I finished. I was talking to my friend Glenn Ballantyne, whom I’ve known since 1968, and he owns a PR firm and an ad agency, and he set me up with a couple of people to see if they could be good cowriters. Neither of them worked out, and after a while, he said, “You know, I could do this with you if you want. I write speeches for governors, and I run political campaigns, and I do a lot of writing in my ad agency.” So, it was a perfect fit, because we’ve known each other for so long, and we’ve had the same spiritual path. We worked six years on it until he was happy with every word and I was happy with every word.

He started with the manuscript I had written, and there was basically a lot of amplifying. Coming from the world of songwriting, I was always very economical in my writing — and even when I do interviews, they want you to get to the punchline quick and then go onto the next question. So he taught me how I to expand and describe and bring the reader along for the journey. And it couldn’t have been a better experience.

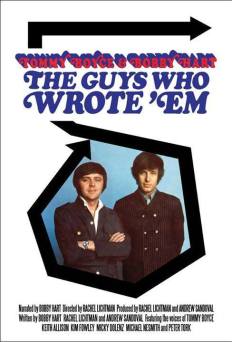

You and Tommy Boyce were also recently the subjects of a documentary film, The Guys Who Wrote ‘Em. How involved were you with the production of the film, and what did you think of it?

You and Tommy Boyce were also recently the subjects of a documentary film, The Guys Who Wrote ‘Em. How involved were you with the production of the film, and what did you think of it?

I loved the film. They did a great job. I was involved from the beginning, and I could see right away that it was different from the other proposals I’d had over the years for a Boyce & Hart documentary. They were coming from a place of being professionals, but also being fans. So I was happy to hand over all my 16-millimeter movies from the ‘60s, that I’d never given to anyone before.

And it’s been unanimously well received whenever it’s been shown, which has been about four times. It’s basically finished; they’re still looking for funding for the licensing of all the music, and for a home for it on a cable network or possibly PBS.

You’ve done most of your work as a songwriter, and now writing your book, with collaborators. In your experience, what makes a good collaborator, and what draws you to a particular collaboration?

I guess most of my life I’ve taken opportunities as they came, rather than seeking them out. In the case of Boyce & Hart, we’d both started in our teens, pursuing solo careers as singers, and in the process, we had to learn to write songs, because where else were you going to find songs for an unknown artist on a small label? So, we had six years of learning that craft, and becoming a little better each time we wrote a song. And in the early stages, we’d help each other out with our songs and not take credit.

Then, Tommy got an opportunity to write for a publisher in New York, and I joined him a couple years later. And at that point is when we became exclusive songwriting partners. It wasn’t because he was a better lyricist, or I was a better melody writer — we both did both. It was because we were friends, and it was so much fun writing together and bouncing ideas off of each other.

Other collaborations have been different. For instance, when I was asked to write lyrics to a movie theme song, it would often come from the movie ‘s composer, and he would just give me the melody on a tape, and I was expected to fit one syllable to every note. And make it sound conversational and singable. And that was a whole different process — that was almost like doing a math quiz until I got the hang of it. It’s still laborious for me, and that’s a totally different relationship.

Rarely have I worked with people who write only lyrics or only melodies. Usually, I work with people who do both. It seems to work well for me.

In the book, you talk about the role that analyzing existing popular songs played in your songwriting, particularly with Tommy Boyce, and the way you drew from the Beatles and other bands to create the sound of the Monkees.

We were always aware of the charts. When we were too poor to buy the Cashbox or Billboard magazines, we would go to the publisher’s office, and we would check out the top 100 and make sure that we’d heard them all on the radio. Then we’d think about what made them hits: “Most of these I love, I don’t know why this one’s on the charts, but a lot of people are buying this record, so let’s figure out what the appeal is.” We were always analytical that way and also analytical in listening all the time to life as it went on around us: listening to conversations, listening for catchy phrases for song titles or song lines. For us, it was a business, and if we were being asked to submit to something for the new Jay and the Americans album, our job was to figure out what they’d done for their last three or four hits and what they would do or not do. So, when we set out to write, we would already have parameters.

As far as the Beatles and the Monkees, that was a different situation. We were told when we got the job from the television producers that they were going to do an American Beatles on television — meaning that they were going to be doing these romps that were visually reminiscent of Help! and A Hard Day’s Night. So, we decided to steer away from the sound of the Beatles, but we did analyze their albums. They always had one killer ballad, they usually had one novelty song that Ringo would sing, and the rest were up-tempo, with great melody lines and killer hooks. So those were the kinds of things we took from the Beatles, but we tried not to be too Beatlesque in the sound.

Do you still listen to current pop music with that analytical mindset?

I do when I listen, but I don’t like I did when I was making my living at that. For the last 10 years, I’ve been working on the book, and now I’m promoting it, and so I haven’t done much writing. The kind of writing I do these days is when I get an assignment or a commission for a movie theme or something like that.

It’s a whole different business now. It’s not like you write songs on spec, and the publishers go out and shop them to the artists. It doesn’t work that way anymore. Songwriters don’t have the opportunities that we had in the ‘60s where you’d get signed to a music publisher who would give you $100 a week, so we didn’t have to get a day job, and we could just concentrate on doing what we loved, which was writing. Today, music publishers are still out there, and they’re still a big business, but they sign primarily artists or record producers. They don’t have to shop the songs, because the artists and producers have already recorded them. There’s not that kind of structure in place, and it’s rough for an unknown songwriter to get signed. I guess Nashville is probably the holdout and the exception.

Speaking of Nashville, I know country music had a huge influence on you as a child.

Yeah, I listened to country in my youth because I didn’t like a lot of what they called popular music at the time. To me, country was much more honest and accessible. So when rockabilly became popular, and Elvis hit the scene, that was the obvious extension of the country side, because the country stations were playing those records — “Be-Bop-A-Lula” and the Elvis stuff and Buddy Holly.

Then, in my mid-teens, I got exposed to the doo-wop groups that were starting to come on the pop radio station. It wasn’t the same stuff that had been popular in the 1940s. Now you had the R&B artists starting to cross over. My first records probably sounded really rockabilly, but soon after that, they had more of an R&B influence.

Do you ever revisit those older records?

I do. I put together a tape of songs from the earliest days, which we were thinking about releasing with the book, but it kind of fell by the wayside. It’ll probably come out in some form. And there’s a small label in England that’s going to be re-releasing the solo album I did in 1978, and there’ll probably be a retrospective of some of that stuff coming out at some point.

Besides country and rockabilly, another big influence on you was the Pentecostal church. Could you talk a little about that?

I grew up in a musical family, in a musical church. As I say in the book, the kind of music they did in our church was a precursor to rock ‘n’ roll. It was spirited and tambourine-shaking, and I loved to go to church because of the music. And I still love Southern gospel music. So that was an influence, and a real help — although my mother was bent on me having classical training, and she had me doing piano lessons and violin lessons. It wasn’t until years later, when my piano teacher gave me a chord book, and I realized, “Now I can play three chords, and I can play most of the songs on the radio.” That was a real eye-opener for me, and I began to take music seriously. I wasn’t into composing as a teenager, but I was able to hone my keyboard skills a little bit.

In the book, you write about how long it took you to pay your dues and find success, while some of your peers started having hit records. What do you think kept you going during that time?

I think it was my background, partially from the church and partially from my parents. I was always told I could do whatever I wanted to if I tried hard enough and not giving up seemed to come naturally for me. I felt left behind when I was still working for a printer, printing record labels for my friends who were having hits. But something kept me going and eventually, it paid off.

After you found success, you were a mentor to other musicians as well — Micky Dolenz says in his foreword that you brought out the best in him as a singer. As a producer and a veteran musician, how do you help musicians perform their best?

I think there’s two elements to it. We talked about honing your craft and paying your dues, and a musician has to learn all that technical stuff. And this applies to any creative endeavor, any contribution you make to the world, even if it seems menial. To make that meaningful, you have to be good at your craft by learning it and practicing it. As a musician, you have to learn how to play the notes, learn what the chords are, and learn the math behind it. But then, if you’re going to be performing, you’ve got to forget all of that — you learn it so that it just comes out automatically, and then you have to put the soul and inspiration into it.

In any creative endeavor, you have the opportunity to do both. You can study until you’re good enough to play in a symphony, or you can study until you’re just good enough to sit around the campfire and create a great atmosphere for camp songs, and enjoy yourself. So you can take it wherever you want. It’s all creativity.

On the other side, when you get the technical part down, and the studying down, that’s there in your psyche, and you say, “Now, how can I let my soul come through a bit and create some inspiration beyond just playing the cold notes. I’m using that metaphor of a musician, but it applies in any endeavor of creativity.

Two themes that seem to come up a lot in the book are your desire to “be somebody” in spite of being an introverted person, and your struggle to find the balance between success and spiritual fulfillment.

That’s the big question of life, and why we’re here — to figure out how to find that balance. It’s not like we want to hide in a cave somewhere and meditate all day, speaking for myself here. I want to find time to meditate and be more peaceful; contribute to the change I want to see in myself; get rid of some of the habits that are not useful to me; create new habits that will take me closer to what I really want; and bring me more fulfillment out of life. So, there’s that balance.

I think that we all have a unique role to play in life, and finding that and playing the part well is the first step. What happened to me was, after I had tremendous success, I realized that that alone wasn’t going to make me happy and bring me the fulfillment I was looking for. So I started looking around and reading books and becoming a spiritual searcher. And I finally found a guru by the name of Paramahansa Yogananda whose words just all seemed to ring true deep inside me when I read them. And so I began following him, and I’ve learned so much from him, and I credit him for basically saving my life. So many of my contemporaries didn’t make it through those troubled waters, those times, and those temptations that come with success, so I feel very fortunate that I was able to find a path that works for me.

What drew you to the work of Yogananda, and how did his ideas mesh with your religious background?

Yogananda has a worldwide organization and millions of followers and churches and so on, but you don’t have to leave your traditional religious underpinnings to learn from him, and to learn his techniques of yoga meditation. And one of his main purposes for coming was to show the similarities of all religions. If you get beneath the outer dogma and ritual, and you get to the core, then all religion pretty much says the same thing: that there’s one God and that the purpose of life is to get to know Him, and get closer to His view of what life should be, instead of your own egoistic one. Yogananda wrote commentaries on the Bible as well as the Bhagavad Gita, showing similarities. So, sure, the spiritual yearnings that I had as a child, that kind of waned as I was out on my own and pursuing a career, that then reawakened — they were all part of the search that I had been on since childhood, and none of it ever went to waste. The relationship that I tried to forge with God all along was never wasted.

You’ve said that when you and Tommy Boyce released your third album, you hoped your listeners would explore the spiritual and social themes of the record as well as enjoying the catchy music. It seems similar to your approach to your book — balancing pop music history with spiritual ideas. What do you hope readers will get out of the book?

Well, I’ve been saying that as you live life, you don’t tend to see patterns. But when you take on an endeavor like writing a book, you start to see patterns emerge. You can see when you made good decisions, or where you made bad decisions that got you in trouble. And as I started to notice these patterns, I decided that I wanted to include in the book some easy-to-reference tips that people might take, that might work for them, because they worked for me. And so we have these pages, that we call “Stepping Stones for the Potholes in Life,” where we address creativity, and visualization, and finding your unique role in life, and so on. Just a page, throughout, in appropriate spots. And so part of the goal became to share lessons learned, that I either learned the hard way, or learned from making good decisions. And that seemed to be to be just as important as telling the music stories, to have some of the stuff in there that’s helped me, and that might help someone else if they choose to try it out.

You and Tommy Boyce became more politically and socially aware as your career went on. Are there any current causes you feel passionate about?

Well, I don’t know that I was ever too political. You’re right; Tommy and I worked on the campaign for Robert F. Kennedy, which mainly came from our love for his older brother and the belief in the things that he was saying, which seemed to be so much less “establishment”-centered. But of course, that didn’t work out, because of his assassination.

Our other big cause was getting the voting age lowered to 18, because the draft was in effect, and 18-year-olds were shipped off to Vietnam to fight and would often die for a cause they may or may not have believed in and didn’t have any input in electing the politicians who were making those decisions. So, that was a big thing we believed in then.

Today is different. One cause is the environment, which I think we’re all starting to wake up to, certainly in California, where we’ve lowered our usage of water voluntarily, about 27%, in the last year or so, because the water just isn’t there. And the climate is changing — there’s no denying that — the big discussion is whether it’s because of something people are doing or because of some freak of nature. But I feel like we need to do our part, just in case the scientists are right in saying that we need to reduce what we’re taking from the planet and the pollutants that we’re putting into the environment. Because I’ve got kids and grandkids that are the inheritors of all this, and that’s important.

I also have strong feelings about equality for everybody — social and economical. As I’ve heard frequently, the playing field should be the same for everybody.

You’ve said that our job in life is to find our own part and play it. What do you think your part is now?

To do what I’m doing. It started with the book — it was something I’d wanted to do for a long time, because I’d been asked about these stories so many times, and we wanted to flesh them out. And it’s been gratifying to hear people saying things like, “I really felt like I was there with you.” That was the intent, to bring the reader along on the journey and make it entertaining and interesting but also to be a little educational. It’s not a self-help book, but you can find things there, and a lot of people have been telling me that they’re benefiting from some of the tips in there. So Glenn and I will be doing speaking engagements, talking about the spiritual things we brought up in the book, and we’ll probably be doing more writing. So between the writing and the speaking, that seems to be the future right now.

Bobby Hart’s book, Psychedelic Bubble Gum: Boyce and Hart, The Monkees, and Turning Mayhem Into Magic, is available now on Amazon. For more information, including the latest news about The Guys Who Wrote ‘Em, head over to bobbyhart.com.